Corey Erdman: Can't predict Canelo-Crawford based on last fight — history proves it

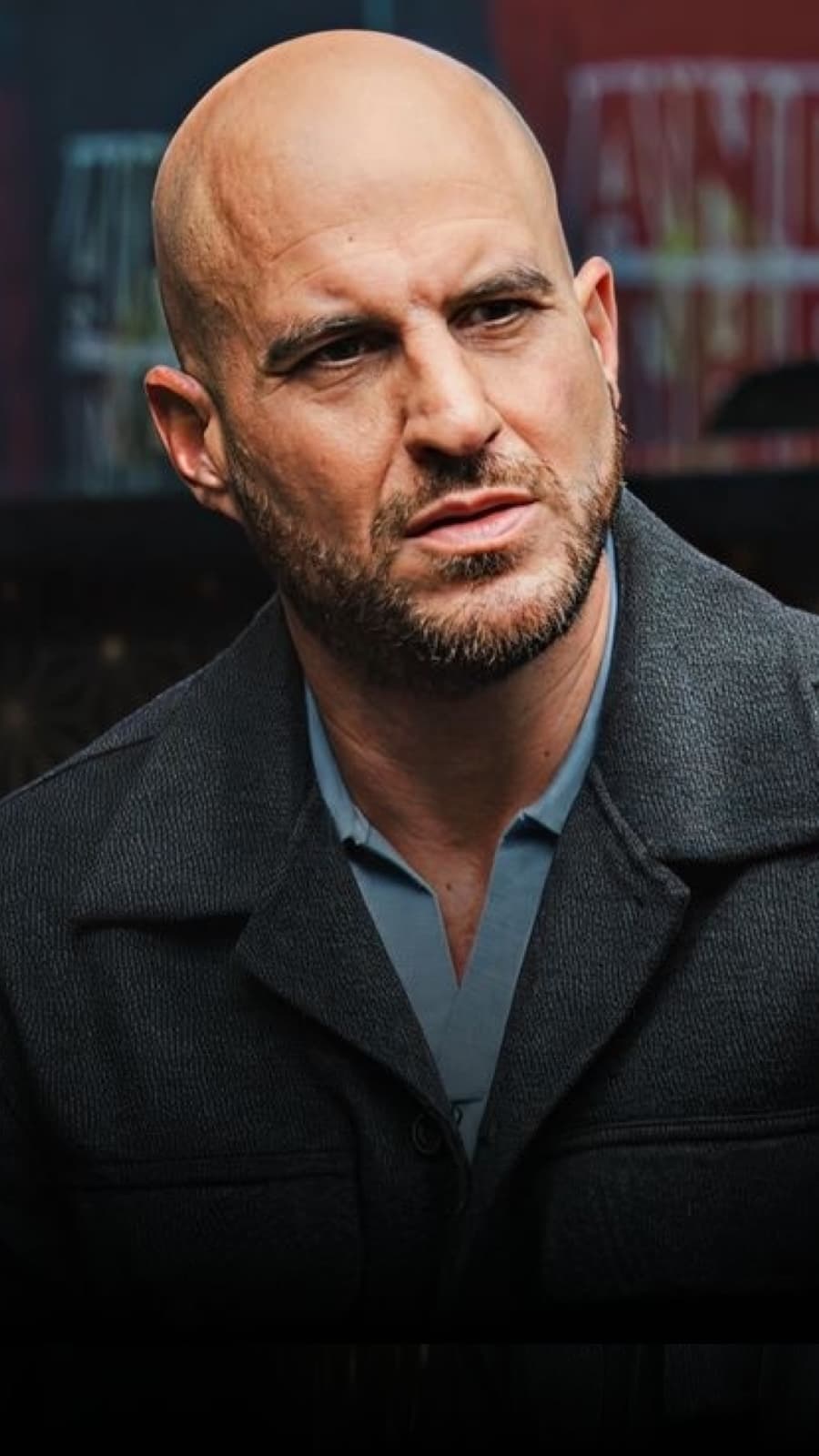

Corey Erdman

Aug 23, 2025

7 min read

With all-time greats who have conquered so much, being unmotivated is a real thing and could explain Canelo Alvarez's snoozer vs. William Scull and Terence Crawford struggling against Israil Madrimov. Ray Leonard, Salvador Sanchez and Evander Holyfield...

The upcoming super fight between Canelo Alvarez and Terence Crawford represents many things. A clash between two of this generation’s best, the biggest boxing match on U.S. soil in the better part of a decade, and a paradigm-shifting collision that will introduce a new promotional powerhouse into the boxing ecosystem.

However, it is not a fight that sees either fighter entering the ring on the back of a career-best performance. Last summer, Crawford moved up to 154 pounds to win a close, competitive decision against Israil Madrimov in Los Angeles.

Taking all of the challenges Crawford faced into account — a new weight division, ring rust and a tricky stylistic proposition — it was the first time Crawford hadn’t been able to simply impose his will and ultimately bully his opponent into their own demise. As a result, some observers questioned whether Crawford had reached his physical peak and whether his best nights were behind him.

In Canelo’s case, he’s coming off a dreary unanimous decision win over William Scull that set CompuBox records for the wrong reasons, ones pertaining to offensive inactivity. Of course, much of the blame can be attributed to Scull, who mostly chose to lap the ring in avoidance of contact, but the performance nonetheless prompted questions about Alvarez’s ability to cut off the ring and level of motivation in the later stages of his career.

But questions have been asked of great fighters based on their most recent performance going into career-defining nights many times in the past, and they have been roundly dismissed as nothing more than observers falling for red herrings. In fact, one could argue that to have the longevity and level of success required to be regarded as a Hall of Famer, as Alvarez and Crawford will be the moment they retire, a fighter must wade through these periods of turbulent doubt and emerge on the shores at least once in their careers.

Perhaps the most obvious example of this in boxing history is Sugar Ray Leonard, who entered his era-defining fight against Marvelous Marvin Hagler in 1987 with his fair share of doubters, all of whom had sound reasoning for feeling the way they did toward the 4-1 underdog. Leonard hadn’t fought since May 1984 when he stopped Kevin Howard in nine rounds. Although Sugar Ray prevailed in that fight, he was dropped for the first time in his career in the fourth round, and at the time of the stoppage, one judge had it a one-point fight.

It wasn’t just writers who doubted Leonard and the sensibility of his intention to face Hagler next.

"There's no sense in fooling myself or anyone else. It's just not there. I just can't go on and humiliate myself. I fought with apprehension. I had fear for my eyes. I had fear for my whole body,” said Leonard following the fight.

Leonard left the sport for three years, ironically, only deciding to come back after watching Hagler defeat John Mugabi from ringside in 1986. As Leonard has told it, he was sitting beside Michael J. Fox and said out loud, “I can beat Hagler.” Although retroactively the win over Mugabi is celebrated, in real time, Leonard saw Hagler “being outboxed” by Mugabi in certain rounds, sensing a weakness he could exploit.

Leonard would go on to win Ring Magazine’s Fight of the Year, Upset of the Year and later Upset of the Decade, silencing the doubt that was internal and external. Of course, it’s a fight that is still debated today, but even if the result had gone in Hagler’s favor as many feel it should have, it too would have supported the thesis here as well, that doubting a great fighter on the back of a perceived shaky performance can be a fool’s gold. In an alternate universe, Hagler’s difficulties with Mugabi would have just been a mirage en route to the Marvelous one being declared the true King of the Four Kings.

One could also point to Salvador Sanchez as an example of a fighter whose finest hour came a fight after one in which his star appeared to have dimmed. A few weeks removed from the anniversary of his tragic passing, plenty of tributes have been shared about one of Mexico’s most celebrated boxing idols, many centering around his brilliant victory over Wilfredo Gomez. Sanchez entered the bout as the reigning Ring and WBC featherweight champion, but also as the betting underdog. The main reason, of course, was that Gomez was regarded as an unstoppable wrecking ball who was on a historic run of knockout victories in world title fights.

Sanchez was also coming off what Los Angeles Times writer Richard Hoffer described as an “off-key” and “lackluster” performance against the unheralded Nicky Perez a little more than a month earlier.

“Sanchez, who has appeared to be the consummate boxer in five title defenses, was something less than sharp Saturday night, boxing three pounds over the 126-pound featherweight limit,” wrote Hoffer. “The same boxer who made the feared Danny Lopez look like he had run into a Cuisinart in winning the title in 1980 was lunging and missing. Also, he was getting hit a lot.”

Gomez was there to taunt Sanchez in the ring immediately afterward, and kept up the trash talking to the point that he enraged the typically even-keeled and respectful Sanchez, prompting an all-time great chilling line: "You had better take your picture before the fight because after I get through with you, you won't recognize yourself."

Sanchez stopped Gomez in eight rounds in an all-time great fight and a landmark moment in the Mexico-Puerto Rico rivalry, leaving the ring with his title and only one regret: “I wanted to punish him, to beat him for 15 rounds.”

Perhaps Sanchez needed Gomez’s needling to find the level of viciousness he unleashed in that fight. This is a common theme when it comes to the many examples of fighters turning things around when it matters most, the need for a little added motivation. One never likes to accuse a prizefighter of complacency, especially when the conceit of entering a fight is to risk one’s life, but there are no doubt nights when fighters are more motivated than others.

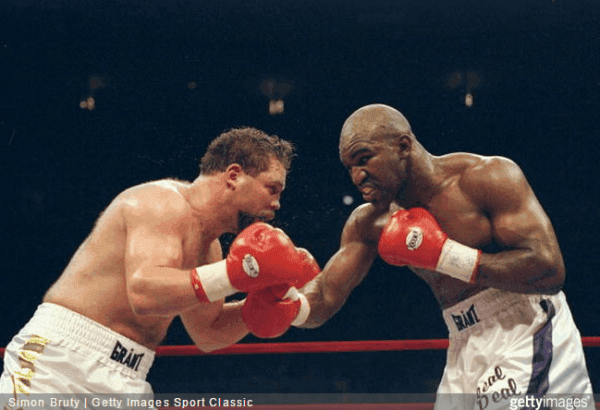

Such was the case on the night — and ultimately nights, plural — that Evander Holyfield faced Mike Tyson. Holyfield was two fights removed from a loss to Riddick Bowe and a fight removed from a forgettable outing against Bobby Czyz when he faced Tyson for the first time. Bookies listed Holyfield as upwards of a 25-1 underdog, as Tyson promised fans that their hot dogs wouldn’t get cold if they paid for a ticket to the fight, suggesting it would be as short and one-sided a fight as Vegas was touting.

What he and very few people hadn’t considered was that for Holyfield, Tyson was the North Star, a monster he’d been thinking of slaying since they first met in childhood, the one adversary who could compel him to summon something special. Holyfield dominated and stopped Tyson in 1996 and won again in memorable circumstances the next time out, at least in part contributing to the psychological deterioration that led to Tyson biting part of his ear off in ’97.

In the case of Canelo and Crawford, it’s fair to say that neither man was fueled with the level of motivation they will be on Sept. 13 in their most recent bouts against Scull and Madrimov. Elite athletes are always motivated, sourcing energy from a variety of renewable sources, but even for the most doggedly determined, those mines can get a little barren, or the descent into them a little more laborious than before. Give them a hint that the treasure trove full of not just all the gold, but the status and legacy they’d dreamt of is within however, and the true greats will dig deeper than ever before.

So discount Canelo and Crawford at your own peril, knowing that if they are the generational greats we know them to be, there’s a good chance one — or both — of them has something special saved up for next month.

Analysis

Noticias de combate

Corey Erdman

Next

Jai Opetaia Defends Ring, IBF Cruiserweight Titles vs. Huseyin Cinkara On Dec. 6

Can you beat Coppinger?

Lock in your fantasy picks on rising stars and title contenders for a shot at $100,000 and exclusive custom boxing merch.

Partners