Corey Erdman: How Mackie Shilstone, Michael Spinks Revolutionized Moving Up In Weight

Aug 15, 2025

11 min read

When Terence Crawford signed to face Canelo Alvarez, according to Shilstone, his team contacted him. Although the two won’t be working together, it’s evidence that if you want to do something physiologically extraordinary in boxing, Mackie Shilstone is...

At 74, Mackie Shilstone is out in the Louisiana heat at a local track putting himself through a football-style sprint workout, running intervals of increasing length moving up from 100 meters upwards then back down again.

Earlier in the morning, he did a weightlifting circuit in his fully stocked home gym. As he gets back to his house, he walks through his hallways lined with degrees and awards to his desk chair, where on occasion he’ll stand up and windmill his legs over the seatback in a makeshift hurdlers’ warmup. As you watch a man approaching his eighth decade on the planet windshield wiper his legs above head-height, it’s clear that you should listen to whatever he has to say about health and fitness.

The proof that we should listen to Mackie Shilstone has been in the protein pudding since the 1980s. It’s been on the fields — ones for play and for battle — courts, rinks and squared circles in the forms of some of the most decorated athletes and military members in history. That Arnold Schwarzenegger once worked out in Shilstone’s backyard gym may not even rank in the Top 50 of his most impressive anecdotes.

He discussed working with Terence Crawford, according to Shilstone, as the career junior welterweight and welterweight (140/147) moves up to fight undisputed champion Canelo Alvarez at super middleweight (168) on Sept. 13 in Las Vegas on Netflix.

But the man who is now described as America’s most influential sports performance specialist wouldn’t have a Rolodex full of the most famous clients imaginable if it weren’t for boxing. And if it weren’t for Shilstone, boxing might still be stuck in the Stone Age when it comes to training and nutrition.

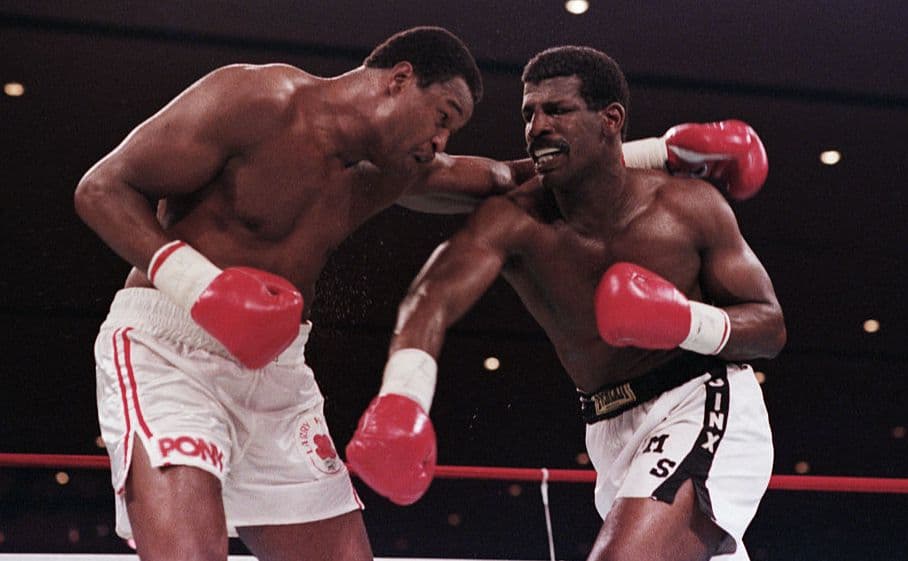

Shilstone’s entry into the broader public consciousness came in 1985, when he helped Michael Spinks move up from light heavyweight to defeat heavyweight champion Larry Holmes. Shilstone had worked with Spinks for previous fights as he was cutting weight, but was simply, as he likes to say in modesty, a rung on the ladder that wasn’t receiving any attention.

However, once Spinks signed up for the Sisyphean task, everyone wanted to know how in the world he was going to pull it off — not just winning the fight but putting on the weight. Once he completed that task not once but twice, defeating Holmes in back-to-back bouts, everyone — and talk to Shilstone long enough to hear who he’s worked with and you will indeed believe it is everyone — wanted the secrets of Mackie’s magic.

“It started in 1982. I was working on my MBA at the time, I already had two other degrees, and I was helping a man named Don Hubbard. Don Hubbard owned part of the Michael Spinks contract. He was from New Orleans," said Shilstone. "He came in, and I was running a medical foundation, specifically for eye disease research and we were all preventatively oriented. And it helped he and his wife so much because the preventive approach to eye disease, it's probably the first medical discipline that recognized the use of citrus bioflavonoids for collagen connective tissue in the eyes.

“So Don Hubbard said, 'I think you can help my fighter.' And so I said, 'What do you mean?' He said, 'Would you be willing to come to the Grossinger's [Resort] in the Catskill Mountains?' And I said, 'Sure, what do you want me to do?' [He said], 'I want you to do what you do, and I want you to get Michael Spinks out of the Army boots, out of what Joe Frazier has been doing.'”

Broadly speaking, strength and conditioning in boxing even in the era of body beautiful fighters in the 1980s was extremely primitive. Big-name fighters such as Sugar Ray Leonard and Marvin Hagler still ran in combat boots (something Leonard admits caused lasting knee issues), restricted water intake during training, avoided weightlifting for fear of becoming bulky and tight and stuck to simply boxing and calisthenics.

There was the feeling that anything outside of these basic principles was not only useless, but actively harmful. In theaters, people watched Rocky IV where one of the main takeaways aside from international unity was that Balboa’s spartan training beats Drago’s scientific approach, further hammering this belief home.

“If you follow Star Trek, Captain Kirk occasionally would go on one of these planets that was back in time. Here comes Captain Kirk landing and he'd have Spock with him. And he would see where they are, and they would make some changes, and then the life went on,” said Shilstone. “I went back in the past. I was Captain Kirk. I went back in time in the archaic training of the boxer.

"I'm talking about the performance training, what I was at the time was an integrated performance specialist. I took over all of the eating, I took over all supplements, I took over all screenings to make sure we were not violating Olympic standards. I took over all the strength training, the interval training, all of that. Back in 1982, it was the first time any boxer was being monitored with heart rate telemetry. They could not comprehend what I was talking about.”

Fighters had been taking off pounds successfully, if not inefficiently, for more than a century by that point. Even a caveman approach to cutting weight would work. Run long miles in heavy shoes, eat less, have some semblance of adherence to consistent hard training and one will lose weight. But moving up in weight in boxing was something that had no rubric.

Generally speaking, fighters would move up because making a given weight was no longer a possibility. Or, if the move up was intentional, the strategy could be boiled down to simply eating a little more. Especially when it came to the heaviest weight class, moving up there was a science that still needed a professor.

History had shown that even great light heavyweights moving up to heavyweight were potentially signing up for disaster. Billy Conn, Harold Johnson, Bob Foster all failed in their attempts in spectacular fashion in eras when the heavyweight champion wasn’t as big as Larry Holmes.

Two fights prior to facing Holmes, Spinks weighed in at 170 ½ for a title defense against David Sears, so it goes without saying that The Jinx was not regarded as a physically imposing light heavyweight.

But if you know Mackie Shilstone, you know that the task of preparing a smaller person to beat a bigger person in combat is one he’d been unknowingly preparing for his whole life.

The son of a World War II hero, Shilstone walks through another hallway in his home dedicated to his father’s military feats. “This,” he says as he points to his medals, “this is what I’m living up to.” His father never wanted him to go into combat, so Shilstone went into academia and collegiate football, where at 5-foot-8 and 143 pounds, he played wide receiver for Tulane University.

Over time, he began to use his scientific and medical research for sports performance. It wasn’t literal war that he was preparing people for (though he would wind up doing that, too), but he borrowed his father’s military ideals and likened his role in athlete preparations to “special forces.” The people he tended to gravitate towards were elite performers who were counted out due to size, or as time went on, age.

“I came to understand that my role was to be a guide, to be out in the front, to be in the darkness and take the person, man or woman, 14 years of Serena Williams amongst others, and waltz them into darkness and give them and keep them on the road. And then at that moment, pass them on and say, 'You've got it now, you can do this,'” said Shilstone.

In Spinks, Shilstone had to help turn a man who was 187 pounds with 9.1 percent body fat when he began camp at St. Mark's Community Center in a church recreation room on July 18, 1985, into an athlete capable of holding up against a heavyweight so dominant that he was on the brink of matching Rocky Marciano’s undefeated record.

As colossal a feat as it would be for Spinks to win, those metrics were somewhat surprising. When Spinks had beaten Sears, his body fat was 4.6 percent, meaning his frame was holding more than enough lean muscle to become a heavyweight, and not one with a soft midsection, either.

The first thing Shilstone did was exactly what Hubbard had requested: No more combat boots or boxing boots for roadwork, and in fact, no more lengthy runs whatsoever. Shilstone purchased Spinks his first pair of Nikes that were used for anything but leisure — actual running shoes.

Rather than slow jogs, he had Spinks perform a series of 440 and 880 meter sprints with a short rest period in between — a 3:1 work-to-rest ratio to replicate the specific demands of a boxing match.

He also brought Spinks into the forbidden lair of boxing: The weight room. He designed what he called an Antagonistic Muscle Circuit for Spinks, a series of exercises that look like a list of movements a bodybuilder would perform, but done one after another with no rest, with Spinks lifting around 80 percent of his maximum weight in that particular motion for sets of around seven.

Spinks went through a gauntlet of chest press, lat pull-downs, leg extensions, leg curls, sit-ups, back arches, chin-ups, dips, leg press and squats. Closer to the fight, he added skipping intervals in between lifts, and plyometric box jumps, which would later become popular in the CrossFit craze.

Eight weeks after camp began, the night of the fight, Shilstone measured that Spinks had put on 15.62 pounds of muscle weight. He entered the ring on Sept. 18, 1985 at 200 pounds with 7.2 percent body fat, both bigger and leaner than he began.

"Michael tells me after the fight, 'Mack, those boxes saved me. Holmes worked me into the corner. And he hit me and I was going down, but my legs automatically sprung up,'" said Shilstone. "It sent chills in me."

Prior to the fight, the curiosity surrounding Shilstone was stirred in with a healthy serving of skepticism. In a 1985 Sports Illustrated piece by Pat Putnam, Angelo Dundee said: “Nutrition sucks. Wind sprints suck, too. And if I catch a fighter of mine near a weight room, he better be able to take a baseball bat to the head.”

On the broadcast of the fight itself, Dundee’s protégé Sugar Ray Leonard said that Shilstone’s techniques wouldn’t work in a reaction to a feature piece about Spinks’ training.

Leonard would apologize to Shilstone and come around to both modern training techniques, and also Mackie himself.

He wouldn’t be the only one, either.

"The next day we get a call and my wife and I are on a plane, Western Airlines being brought into Hollywood. I'm there, we're doing interviews all over the place," said Shilstone. "Now, I wasn't the one that did the fighting, but no one had broken the code. When I got home, I had calls from book agents, Dustin Hoffman, all kinds of people. I'm thinking to my wife, I said, 'What's going on? What did I do?' To me, I'm protecting Michael. It changed the entire course of my entire life."

It would change the course of boxing history, and it wouldn’t be the last time he’d be involved in such a moment. He would go on to be the architect of Roy Jones’ move up to heavyweight to defeat John Ruiz, Andre Ward’s move to light heavyweight to beat Sergey Kovalev, and aided in Bernard Hopkins’ historic run into old age as world champion.

Shilstone said Crawford's team contacted him, although the two aren't working together for next months superfight. But’s evidence that if you want to do something physiologically extraordinary in boxing, Mackie Shilstone is still a man you want in your corner.

And even if he isn’t, a lot of what we know and have come to accept in the world of fight preparation is because of the man who is still doing those same workouts himself well into his 70s.

Shilstone would go on to help Serena Williams and Peyton Manning enjoy second acts in their careers, finding a new niche as the man athletes go to in order to extend their great careers. He would earn rings from the NCAA national championship, World Series and Stanley Cup, and become a go-to specialist for the FBI, Navy SEALS and various Special Forces battalions.

None of it would have happened without Michael Spinks.

“I became this necessity that went from $75 a day in 1982 to $75,000 for the first Spinks fight,” he said.

Analysis

Noticias de combate

Next

Jai Opetaia Defends Ring, IBF Cruiserweight Titles vs. Huseyin Cinkara On Dec. 6

Can you beat Coppinger?

Lock in your fantasy picks on rising stars and title contenders for a shot at $100,000 and exclusive custom boxing merch.

Partners