Corey Erdman

Jan 20, 2025

9 min read

It was 1:58 AM in Kenya when Mike Altamura laid his head down to go to sleep at the end of another day of vacation. He drifted off to sleep rather quickly, so when his phone began to buzz at 2:03 AM with a Japanese number and the name “Mr. Honda” appea...

It was 1:58 AM in Kenya when Mike Altamura laid his head down to go to sleep at the end of another day of vacation. He drifted off to sleep rather quickly, so when his phone began to buzz at 2:03 AM with a Japanese number and the name “Mr. Honda” appeared on the screen, he assumed it was just a dream. As a hardcore fan of boxing who “watches crazy, kooky fights from all over the world” even outside of his profession as a manager and promoter, it wouldn’t be unfathomable to be dreaming of receiving a call from a legendary Japanese promoter.

In the seconds between opening his eyes and pressing the green button on his phone to answer, he ran the informal mental diagnostic tests one does when jolted awake to consider if what was happening was indeed real, and if so, what could the call be about. Altamura had met with Honda a month prior, before his client Ryosuke Nishida’s IBF bantamweight title defense against Anuchai Donsua in Osaka, and had pitched the idea of another client of his, Korean super bantamweight Ye Joon Kim, being added to the undercard of Naoya Inoue-Sam Goodman. Kim, he suggested, would be a good “break in case of emergency” option in the event that Goodman was injured once again. A day prior, their bout had been postponed to January 24 after Goodman was cut in sparring, and Altamura had a hunch that it might not heal in time for the new date. He matched Kim in an eight-rounder against Filipino journeyman Kenny Demecillo, a good showcase opportunity for a fighter who had mostly fought obscured from the gaze of the global audience.

Altamura answered the phone, still in a sleepy haze. Was this what he thought it was?

“I just heard him talking about Goodman, pull out, cut again, and I was like, okay? Then I was thinking in my head, it’s thirteen and a half days out from the fight, is the show going to get postponed?”, recalls Altamura. “And then he’s like, ‘is the Korean’s weight okay?’ Then it started clicking in my head, oh wait, we’re in!”

Within minutes, he was told, someone would be calling him to arrange travel and other documents, but first, he of course had to make a call of his own.

All the way across the Indian Ocean, eight hours into the future time-wise, Ye Joon Kim was doing his morning roadwork, preparing for another day of sparring with former bantamweight champion Jason Maloney in Australia.

“It was a great moment. I thought oh wow, now I must run even more distance than I was planning! I upgraded my schedule for this kind of challenge. I was running six kilometres, but automatically I adjusted to 10 kilometres, as I knew I would need the extra conditioning for this fight,” said Kim. “I was really excited and appreciative. I always felt like I may someday cross paths with Inoue, but for it to become reality is amazing.”

That reality will materialize on January 24, when Kim will indeed face Inoue for the RING Magazine super bantamweight title in a bout aired on ESPN in the United States, as well as Sky Sports in the United Kingdom. Korean outlets have already latched onto the underdog story, in particular citing one sportsbook’s odds that have given Kim the equivalent of a 5% chance of winning.

If one were to argue that Kim defeating Inoue would be the biggest upset in boxing history, they would certainly have a compelling case. The 32-year old is two fights removed from a disputed majority decision loss to the 14-9 Rob Diezel, a punishing affair in the off-the-grid boxing territory of Auburn, Washington. The best wins on his resume would likely either be his most recent triumph over India’s Rakesh Lohchab, or a 2016 win over cult Japanese favorite Yuki Strong Kobayashi. In other words, one doesn’t need a bookie’s insight or an algorithm to know that the idea of him beating a generational great is statistically unlikely.

But if Kim’s chances of beating Inoue are 5%, those odds are a great deal better than the ones he’s beaten to this point. The path he’s taken to his world title opportunity can’t even accurately be described as unlikely, because there was in fact no path for him whatsoever, in his life, let alone in the sport of boxing.

Kim was born in Seoul, South Korea, and raised in an orphanage after being left at the facility when he was five years old. He doesn’t know if he has any siblings or not. Kim was never adopted, something he says he was teased relentlessly about in school, the fact that he didn’t have any parents—in fact, he doesn’t even know what they look like.

In 2015, he told reporter Shin Kang of the Seoul Shinmun that before fights, he thinks of the moments when he was bullied, when he was pushed around in the schoolyard. “When I imagine such bad things and get through the first round, the situation is better than I imagined, and that makes me feel good,” he said.

“Following my debut fight, every time I fought I felt like my old self disappeared and I gradually was becoming a world class athlete. Now I see myself as a complete professional boxer. Boxing gave me a focus and assisted me to overcome the toughest struggles in my life,” Kim told RING Magazine.

Kim had no amateur career whatsoever. In fact, he dropped out of Baekseok University, a prestigious private university, and found his way to the Korean Boxing Club with the goal of becoming a professional fighter like Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao, whom he’d watched on YouTube. His earliest ring nickname, which remains on BoxRec although he doesn’t use it anymore, was Packiweather. Although he had no formal amateur grooming, he was able to somewhat mimic the movements and patterns of Pacquiao and Mayweather even in his early days, flowing between an aggressive southpaw approach and an orthodox shoulder roll. Club director Yong-Hwan Lee immediately noticed his athleticism, and took a liking to Kim, particularly after learning his backstory.

Considering his pedigree, Kim had a respectable start to his career, despite suffering a loss and two draws in his first seven fights. In 2014, he even picked up a WBC youth super bantamweight title. However, not long after that, the Korean boxing scene fractured and changed dramatically. The Korean Boxing Federation (KBF) split from the Korean Boxing Commission after a lengthy power struggle. Kim’s gym was affiliated with the KBF, which the WBC did not recognize as a true commission, and as such, stripped Kim of his youth title. The already fledgling scene was suddenly as far away as it had ever been from the glory years of Korean boxing, when Myung Woo Yuh, Jung Koo Chang and Sung Kil Moon were champions and international stars.

“It is tough in my country as we have very little support for the professional boxing profession,” said Kim. “Boxing was once a very strong sport but now the focus is more on soccer, basketball, baseball, and other sports. I hope someday I can be part of the change to see my country return to being known as a great boxing country.”

Lucky for him, Yuh, who was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2013, felt a similar way about him even back in 2015. Yuh became the vice chairman of the KBF, and at the time, said that he felt Kim was the upcoming fighter with the greatest possibility of reaching the world level. That did indeed turn out to be true. No male Korean fighter has challenged for a world title since Young Gil Bae was stopped by Wanheng Menayothin in a bid for the WBC minimumweight title in 2015. The last male Korean world champion was In Jin Chi, who retired as WBC featherweight champion in 2006. When the KBF formally launched, Yuh put Kim in the first main event, which served as an unofficial start of a new era in Korean boxing.

To try to reach the next level, Kim ventured to Australia to link up with trainer John Bastable at the United Fight Team, where he trains alongside fellow Korean Dong Hoon Jang. The road, as it’s always been for Kang, was still turbulent. In the aforementioned loss to Diezel, it appeared to many as though Kim had reached his ceiling, that he’d built a nice record in the confines of the Korean club scene, but that his tarnishing blemishes were now visible in the brighter lights of the West.

Altamura wasn’t convinced of that, however. He wasn’t officially working with Kim at the time, but had always been tight with his new camp, given that they’re fellow Australians. He knew that for the second time in Kim’s career, he entered a fight fully knowing he needed surgery immediately afterwards—the other being the Kobayashi fight, which he entered with an elbow injury that subsequently required six months of rehab.

Altamura says that he and Bastable started getting calls from promoters and agents telling them to “cash (Kim) out,” leverage his good-looking record to get him a decent bout and then cut ties. Instead, Altamura decided to take the wheel. Not only was he enamoured with Kim as a person, touched by his backstory, but he also felt there was more to him as a fighter.

“I said just let's get him a couple of the right opponents see if he can pull the trigger, engage and assess from there. But you should never be making an assessment from a panicked position, so we kind of clicked, we're on the same page,” said Altamura.

Although the next two opponents he faced, John Basran and Lohchab, were far from world caliber, Kim blew them out. With the Lohchab win, he picked up a regional WBO belt, which turned into the No. 11 ranking with the sanctioning body that he enjoys today—the one that made him a viable replacement opponent for Inoue.

“My right shoulder was in agonizing pain, and was very limited. I have fully recovered from that rotator cuff injury and I believe that has reflected in my last two performances. I feel I am still growing and becoming smarter as a boxer too,” said Kim. “I am an aggressive counterpuncher, and I have a diverse style. I like to use my feet and my defense but I can also stand and trade if needed.”

Kim’s journey from the orphanage to facing perhaps the best fighter on the planet is a tale that Hollywood producers would either find tantalizing or throw out instantly for being too absurd. A self-made warrior, private school dropout, fighting to ward off the ghosts of his past, and to bring not just attention, but honor back to the national boxing scene that helped him discover himself.

Win or lose, this opportunity on its own—the publicity and the payday--has made Kim’s larger objective of opening his own boxing school a near inevitability.

“It is everything. This may be the opportunity that brings attention and the spotlight to what I want to achieve to help young aspiring boxers in my country for many years ahead,” said Kim. “There have been tough moments but I have always held onto the hope that my opportunity will come one day. It has now arrived.”

What might have been just a dream at first is now real life.

Featured News

Noticias de combate

Corey Erdman

Next

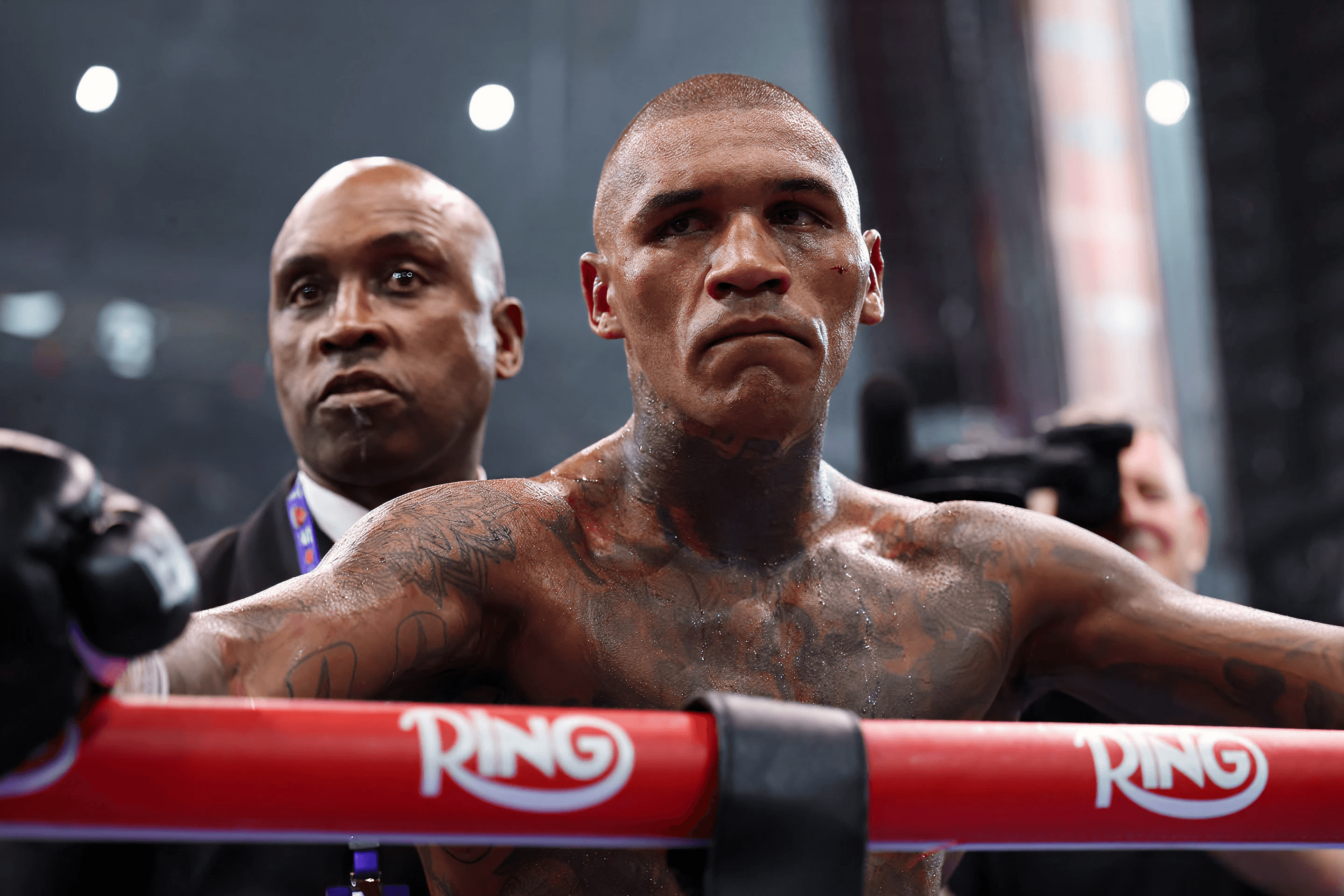

Conor Benn believes he should have won a decision

Can you beat Coppinger?

Lock in your fantasy picks on rising stars and title contenders for a shot at $100,000 and exclusive custom boxing merch.

Partners