Thomas Gerbasi

Jun 6, 2025

9 min read

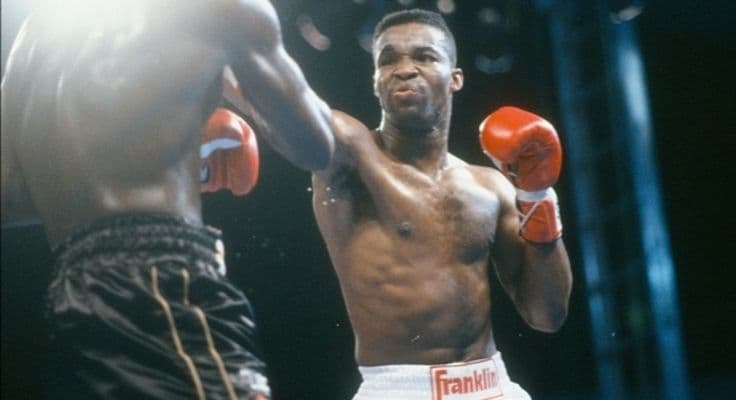

This weekend, Michael Nunn will be in Canastota, N.Y., receiving his induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Boxing fans of a certain age will remember the two-division world champion as an elite member of the pound-for-pound list at 160 ...

This weekend, Michael Nunn will be in Canastota, N.Y., receiving his induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Boxing fans of a certain age will remember the two-division world champion as an elite member of the pound-for-pound list at 160 and 168 pounds.

Yet younger fans might not know who “Second To” Nunn is and wonder why he’s receiving the sport’s highest honor. I’ll leave just one little factoid to answer that question:

Nunn fought Marcos Geraldo in his eighth pro fight.

OK, who was Marcos Geraldo? First off, he’s not someone a prospect fights with less than 10 bouts. By August 1985, when Nunn faced the rugged Mexican veteran, Geraldo had already been in the ring 90 times and had thrown hands with the likes of Thomas Hearns, Marvin Hagler and Sugar Ray Leonard, going the distance with the latter two.

Nunn stopped him in five rounds.

“I whooped the guy, but this man was tricky,” laughs Nunn. “And then he had a sneaky right hand. He caught me with a couple right hands and I said, 'This old guy can crack.' He was an old veteran from Mexico that just knew how to fight. He knew how to set you up and trick you because he had so much more experience than I had.

"He'd been in the ring with Tommy Hearns, Sugar Ray Leonard and Marvelous Marvin. But it was something we wanted to do. We really wanted to beat this man because of his credentials and the fact that he'd already been in with the best of the best. I wasn't going to really show him that I was a young hotshot because he's already been in with some of the best fighters ever. But it made me motivated to really go out and fight him and fight him hard and want to beat him.”

That’s really all you need to know about the proud native of Davenport, Iowa. He was the best of the best for a long time, a smooth boxer with pop, and he fought and beat the best of his era in an era that most consider boxing’s last true golden age. But what got Nunn to the Hall of Fame was that something in his chest that set him apart from most. You can call him a boxer, but deep down, he was a fighter. No challenge was too big for him, whether it was that early test against Geraldo, or his later wins over a Who’s Who of boxing in the '80s and '90s.

Whether that’s something in his DNA or a trait developed over a stellar amateur career that nearly landed him in the 1984 Olympics and 62 pro fights is open to debate. Nunn thinks it might be something in the water in Davenport, not exactly a hotbed for boxing, but a place that put a chip on his shoulder when he traveled outside state lines to fight.

“There's never been a champ from Iowa. I'm the first,” said Nunn. “So that put me on the Mount Rushmore of Iowa, and it motivates the boys and girls that are coming up. It gives them something to work for. Because when I turned pro 40 years ago, they said, ‘Hey man, you’re from Iowa? They're going to kill you.’ But I was shooting my best shot and I'm swinging for the stars. So this is just motivation for the kids that are from Iowa. That don't mean they can't do nothing. I want to change their mindset because once upon a time they told me the same thing: ‘You can't do this, you can't do that,’ but we overcame all that. You’ve got to be tough in your mind, you got to bust your butt, say your prayers and go out there and keep swinging.”

Over a pro career that spanned from 1984-2002, Nunn did all of the above, resulting in middleweight and super middleweight world titles. Along the way, he beat Curtis Parker, Alex Ramos, Frank Tate, Juan Roldan, Sumbu Kalambay, Iran Barkley, Marlon Starling and Donald Curry. The Tate win in 1988 was particularly satisfying, given the amateur history between the two.

“We had a rivalry going on through the amateurs because we fought three times and I thought I beat him all three,” said Nunn. “But unfortunately, out of three events, he won twice, and I won once. So we got ready to fight for the world middleweight championship and I said, ‘Well Frankie, I got to tighten it up on you tonight. You’re up on me two to one, and I got to straighten it out.’ And I just wanted to obliterate him and beat him.”

There was more to it, as Nunn was supposed to compete for a spot on the '84 U.S. Olympic team at 156 pounds. USA Boxing wanted Tate to compete in that division, so they asked Nunn to move up to 165, where he lost to Virgil Hill. Tate won gold at 156, and this was Nunn’s shot to even the score.

“That was my motivation the whole training camp, just to get in tip-top shape and go out and execute,” he said. “At that time, that was the second to last 15-round title fight. So we were super conditioned, and I was a machine. I wasn't going to stop punching.”

In the ninth round, Nunn halted Tate to win the IBF middleweight title. He successfully defended the belt five times, and the talk of the boxing world was Nunn fighting one or more of the “Four Kings” — Hagler, Hearns, Leonard and Roberto Duran. Sadly, none of those fights materialized for various reasons.

“When I was pound-for-pound back in ‘88 and ‘89, I just wanted to fight Sugar Ray, Tommy Hearns and Duran,” said Nunn. “I never wanted to fight Marvin Hagler because Marvin used to give me a lot of pointers and stuff and I didn't want to say, ‘Well, he got old and now I want to fight him.' I ain't no coward like that. I have love and admiration for Marvelous Marvin Hagler. He was a great man and showed me a lot of things and told me a lot of things.

"But Sugar Ray, Tommy, and Duran, that's the only thing I miss about boxing is not getting the opportunity to fight those guys. But other than that, I fought 62 professional fights, won 58 of them and lost four. I think I only lost one, but hey, that's the way the judges seen it and that's just the way it is. I don't complain. Whatever happened, happened. They said it couldn't be done, and we've done it. But my only regret is not getting the opportunity to fight Sugar Ray, Tommy and Roberto Duran. And I'm great friends with all of them. I love them, they all inspire me, they’re wonderful champions and I just wanted to test my skillset with them. Not saying I couldn't beat them or could have beat them, but just wanting to see. And we all had the opportunity to do it, but they never really wanted to fight me.”

It was understandable, because when Nunn was on top of his game, he was a nightmare matchup for anyone. But, in boxing, all good things always come to an end. Nunn lost his title in 1991 when he was stunningly upset by James Toney.

He moved up to 168 pounds, where he won a second world title by defeating Victor Cordoba a year later, and after losing that belt to Steve Little in 1994, he migrated seven pounds north to light heavyweight. There, he lost a split decision in Germany to WBC champion Graciano Rocchigiani, but compiled six more wins before he was arrested in 2002 on drug trafficking charges.

Two years later, he was sentenced to 292 months in federal prison. If you’re doing the math at home, that’s more than 24 years.

Nunn’s boxing career was over. He was 40, probably still had another title run in him, but after being released in 2019 after serving 16 years he has not only taken responsibility for his actions but refuses to be bitter.

“I did my time with a smile and people tell me, 'Hey man, you unusual,'” said Nunn. “But I look at it in a positive fashion because when I was in the streets hustling, doing the stuff that I was doing, I could have been murdered or could have murdered somebody or had a shootout with the FBI or whatever. So whatever was supposed to happen, happened. And I just thank God for getting me through it. I’ve got my faculties, my mind, and I can still do things. God's been good to me. I'm a no-excuse guy.”

And maybe, just maybe, if you’re looking for a silver lining in this chapter of his life, it’s that he was taken from boxing before boxing got to take something from him. Talk to the 62-year-old today and he can reel off dates, names and details from his career with a clarity that will make anyone blush, and that’s a beautiful thing because it’s rare.

Several of his peers from back then can’t say the same thing, which is the dark side of this sport. Nunn, however, is a survivor. While everyone was reintroduced to him after his release, the true note of appreciation for the Iowan’s career came in December when the IBHOF’s Ed Brophy gave him a phone call.

Michael Nunn, Class of 2025, International Boxing Hall of Fame.

“I knew it was coming, I just had to wait my time,” said Nunn. “You’ve got to understand I was gone for 16 years and six months. ... You can't be incarcerated and be on the Hall of Fame ballot. So I had to put things in consideration. You got to be free in society to be able to do it, so they explained everything to me, and I understood it wholeheartedly.

"But the most important thing, there's no greater time than the present. I'm thinking without my incarceration, I might've been in maybe five years ago, eight years ago. But hey, I'm in there now so I'm not even going to worry about it. We’re looking up, not down, and we're moving forward, and not backwards. I'm just glad to be able to get the phone call, and I’ll remember it for the rest of my life.”

News

Fight news

Thomas Gerbasi

Next

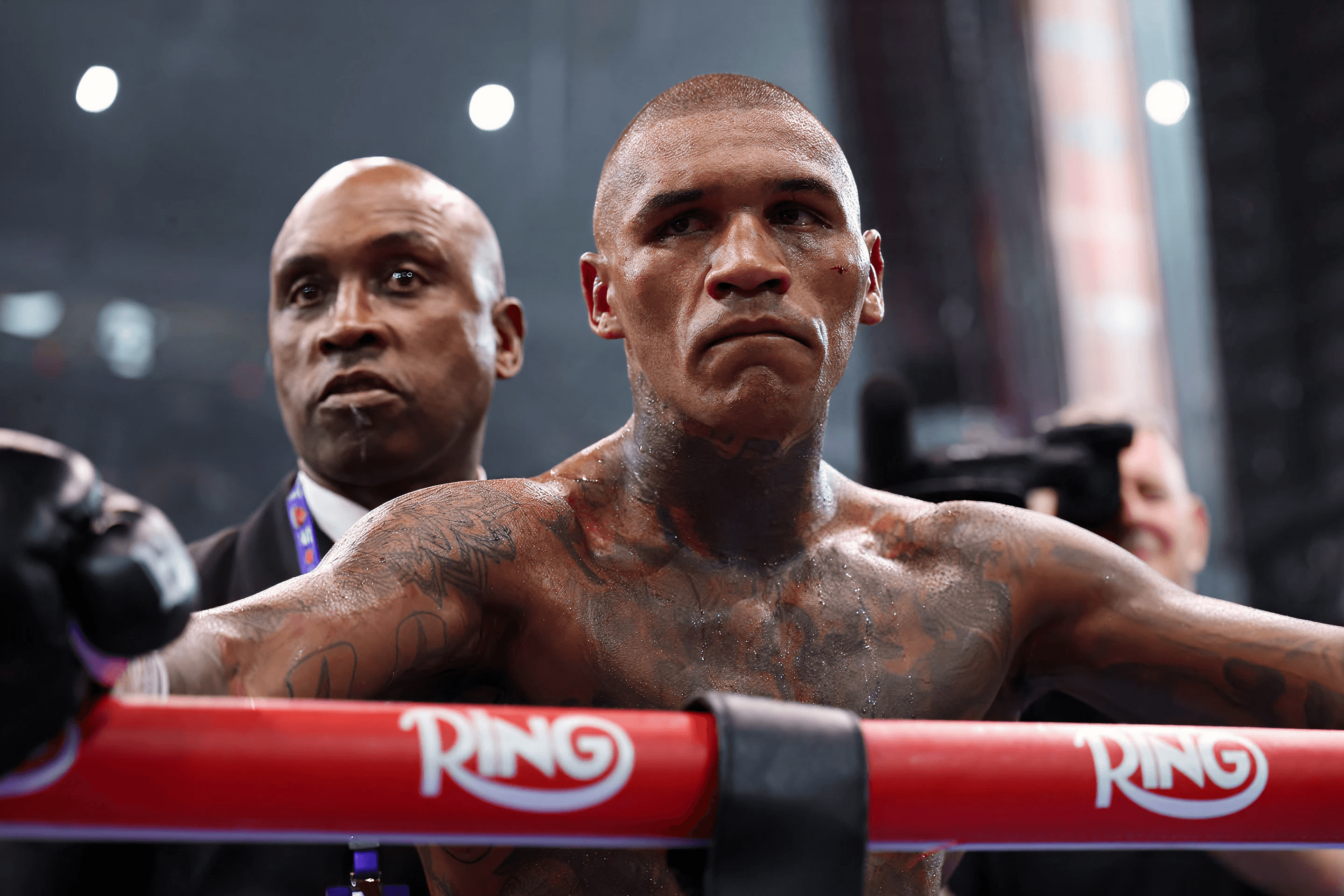

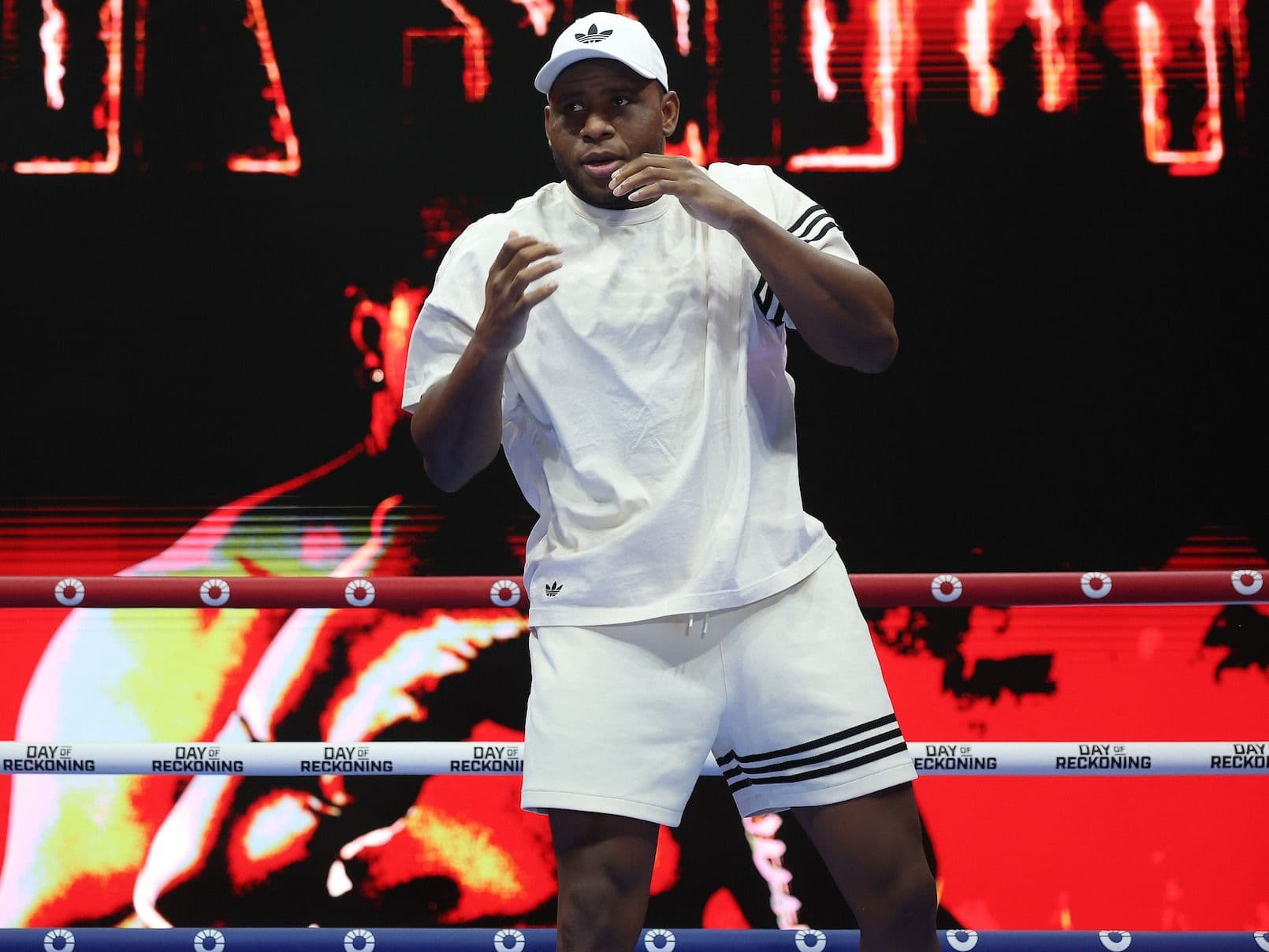

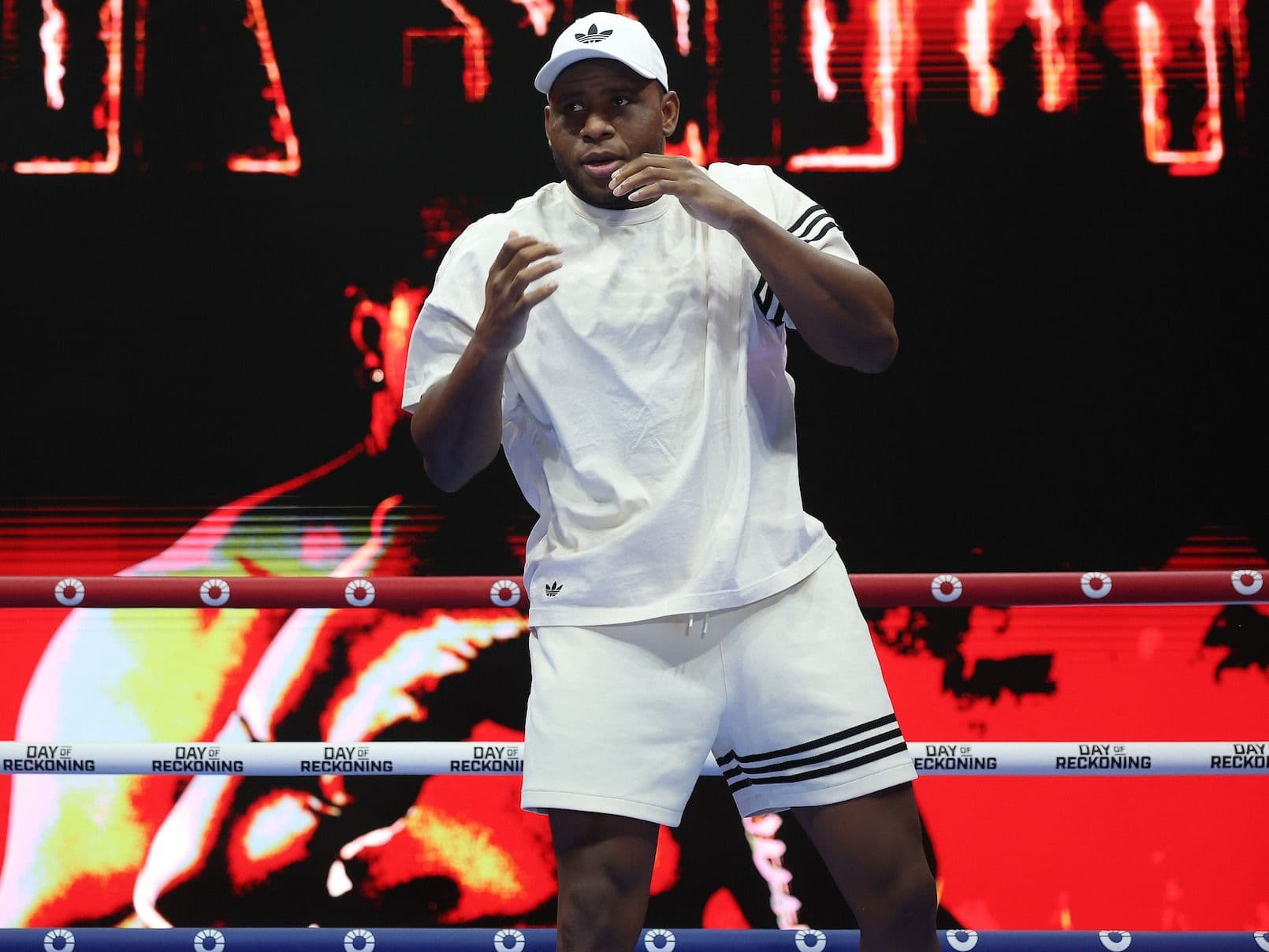

Conor Benn believes he should have won a decision

RELATED ARTICLES

The Ring Roundtable: 5 key questions before the biggest fights on January 31

Latest News

Declan Taylor: Will Josh Kelly's rough ride reach its dream destination?

Latest News

Frank Sanchez-Richard Torrez reach deal on IBF eliminator, late March targeted

Latest News

RELATED ARTICLES

The Ring Roundtable: 5 key questions before the biggest fights on January 31

Latest News

Declan Taylor: Will Josh Kelly's rough ride reach its dream destination?

Latest News

Frank Sanchez-Richard Torrez reach deal on IBF eliminator, late March targeted

Latest News

Can you beat Coppinger?

Lock in your fantasy picks on rising stars and title contenders for a shot at $100,000 and exclusive custom boxing merch.

Partners