Oscar Collazo Wants The Big Bucks In The Lightest Weight Classes

Mar 29, 2025

4 min read

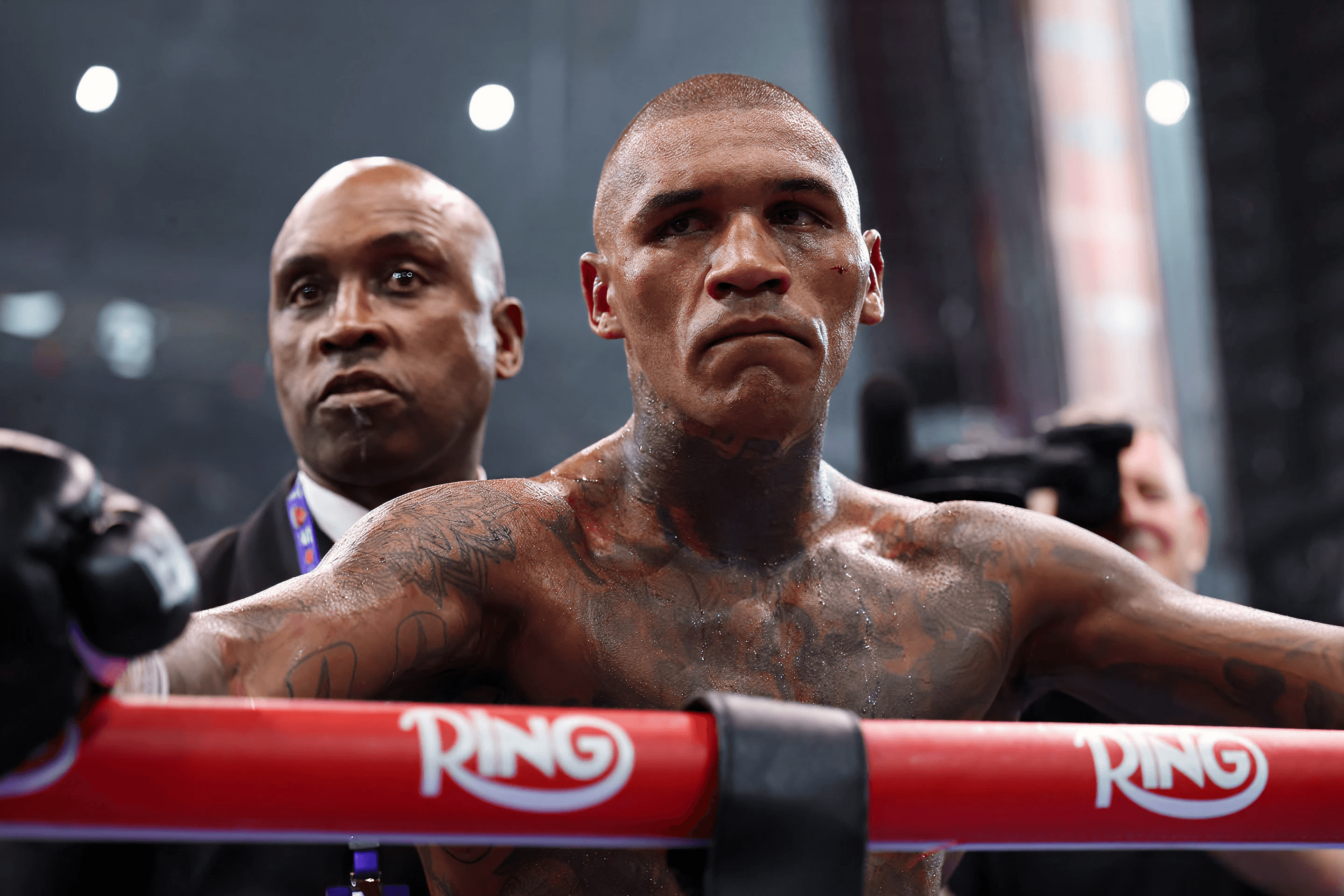

Oscar Collazo has his head in his palms immediately when asked about his beloved New York Yankees outlook for the 2025 Major League Baseball season. Growing up, Collazo dreamed of being the shortstop for the Bronx Bombers long before he became one of t...

Oscar Collazo has his head in his palms immediately when asked about his beloved New York Yankees outlook for the 2025 Major League Baseball season. Growing up, Collazo dreamed of being the shortstop for the Bronx Bombers long before he became one of the biggest bombers the strawweight division has seen in years, and has maintained his fanaticism into adulthood.

“I don’t know how we keep getting injured, I dunno how we’re gonna beat the Dodgers, but I still have faith,” he says shaking his head.

Finding a way to beat a powerhouse like the Dodgers in the World Series would seem as difficult as Collazo’s even more personal mission of bringing greater visibility and respect to the 105-pound division. In fact, the same issue he’s running into now is the same one he had in his pursuit of a career in Pinstripes: People think he’s too small.

This Saturday, Collazo will make the first defense of his Ring Magazine strawweight title against Edwin Cano in the co-feature of a DAZN-streamed event headlined by William Zepeda and Tevin Farmer. The billing itself, frankly, and with no disrespect to Zepeda and Farmer whose rematch is a terrific fight deserving of a top bill itself, is indicative of the plight Collazo and fighters his size face. In any circumstance above 118 pounds, in all likelihood, a Ring and unified title fight would command the kind of buzz and attention that would make it an automatic main event. But Collazo, like the great predecessors whose achievements he’s now chasing, is hoping he can be the strawweight to finally change the narrative.

In his last fight, Collazo unseated boxing’s longest reigning titleholder at the time, Knockout CP Freshmart, with an emphatic seventh-round TKO victory in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. After eleven title defenses, Collazo finally wrestled the stronghold Freshmart had on the Ring title, which also hampered the division’s visibility. With only two exceptions prior to facing Collazo, Freshmart didn’t fight outside of Thailand, where no major network in the Western world has aired a boxing broadcast from in some time. The fights themselves are easy enough to find for boxing hardcores, generally aired for free on Thailand’s Channel 7 YouTube channel, but that isn’t exactly a place the median boxing fan is trained to look. Combine that with the implicit bias that has existed in the boxing marketplace for many years—that fights below bantamweight are of a lesser calibre, or not worth paying attention to—and the division as a whole has struggled for recognition and respect mightily over the last decade or so.

"I just want it to be like the time with Michael Carbajal made millions, made good money. I want that. I want to make a statement, a change of the mentality of everybody, because everybody says the lower weight classes are boring, they don't have power," said Collazo. "I'm here to change that. We want to make that big money, millions, like Chocolatito (Gonzalez), Carbajal. That's how I visualize myself in this weight division."

The arguments that strawweights, or any of their neighbouring lower weight classes, lack excitement or power punching is at best rooted in a lack of familiarity, and at worst willful ignorance. No one who has watched Francisco Rodriguez Jr. and Katsunari Takayama chuck 1913 punches at one another in 2014 could walk away thinking the division is incapable of exciting fights—if anything, you might think that lighter fighters are in fact predisposed to more action.

And no one who has watched Collazo dispatch of five of his last six opponents early could think that this 105-pound man can’t punch.

“It’s like from 115 up, people are like yeah, okay,” said Collazo, “but a lot of those big names (in that division), they fought at 105, 108 too.”

Aside from overall exposure, a few other things have plagued the division, and no doubt added to the lack of attention. For one, it’s the sport’s youngest weight class, only established in 1987, meaning there are fewer historical reference points for fans. Even the indisputable all-time greats that spent the bulk of their careers at strawweight, Ricardo Lopez and Ivan Calderon, spent the bulk of their time on American cable fighting on pay-per-view or premium cable undercards. In Calderon’s case, it took until his final few fights for him to headline a pay-per-view—independently distributed by Integrated Sports.

There’s also been the issue of continuity. Lopez, Calderon and Freshmart represent rarities in terms of longstanding stalwarts at 105. Generally speaking, 105 has been an early career pass-through for fighters to compete in before their bodies grow, or they want their bank accounts to grow so their bodies act accordingly and venture upwards.

It’s the ultimate chicken and the egg scenario. But Collazo wants to establish himself as the top chook, the one that the other divisional champions and budding stars want to fight, and its future prospects want to stick around to ensure they can fight. In particular, Collazo wants bouts against Melvin Jerusalem and the Shigeoka brothers. Rather than entertain the idea of moving up in weight to chase bigger names or checks, he wants to bring them to him, to create an ecosystem of rivalry and lineage like the higher weight classes enjoy.

“We only need the push from different promoters, you know, Oscar De La Hoya, Miguel Cotto, and all around, all the promoters that got fighters in lower weight classes to push that mentality for the lower weight classes. To make a difference. Like, we suffer, we box, same as the 140, 147-pound fighters. We suffer too. The punches hurt the same,” said Collazo.

Featured News

Noticias de combate

Next

Conor Benn believes he should have won a decision

Can you beat Coppinger?

Lock in your fantasy picks on rising stars and title contenders for a shot at $100,000 and exclusive custom boxing merch.

Partners