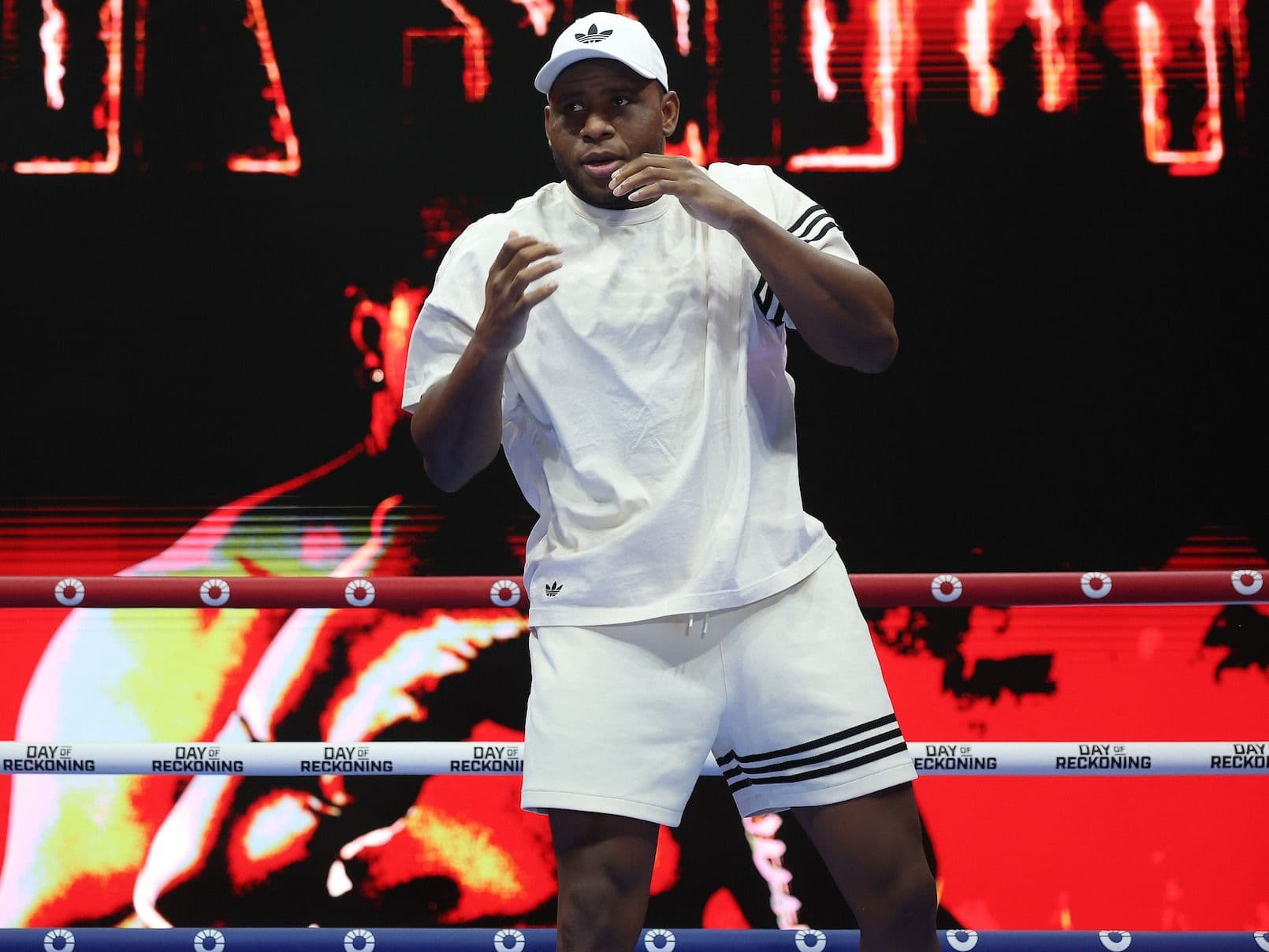

Meet Leo Atang - The Teenage Heavyweight Dismissing Comparisons To Moses Itauma

Declan Taylor

Jun 17, 2025

5 min read

Leo Atang cared far more about rugby and football the day he decided to put the boxing on in his mum’s front room for the first time. That night, Anthony Joshua climbed off the canvas to stop Wladimir Klitschko at Wembley Stadium and, up in York, one 1...

Leo Atang cared far more about rugby and football the day he decided to put the boxing on in his mum’s front room for the first time.

That night, Anthony Joshua climbed off the canvas to stop Wladimir Klitschko at Wembley Stadium and, up in York, one 10-year-old’s life would change forever.

“I had tried every sport there is,” Atang, now 18, tells The Ring. “But then I watched that AJ-Klitschko fight and I thought ‘I want to give this a go’.

“Everyone in school knew who AJ was but I had never seen any of his fights until that one. But straight away I knew I had to try it.”

Incidentally, Joshua was already the age Atang is now when he first walked into the Finchley Amateur Boxing Club for an evening session that would ultimately change the course of British boxing history.

Atang was straight into the gym and, by the age of 13, was preparing for his first amateur bout. “I was 55 kilos then,” laughs Atang, now a fully fledged heavyweight.

“It was at the Bradford Hotel and I was very nervous, I had never seen anything like it before. Everyone warming up in the same room then out into the suite with fancy lights and tables everywhere.”

With that in mind, it has been a rapid ascent across the last five years for Atang, who also had to contend with the Covid-19 lockdown which threatened to end his boxing career just four bouts in.

It was a period where a number of promising sporting careers, never mind boxing, would have fallen by the wayside given the restrictions enforced across the UK but Atang sensed an opportunity.

“What motivated me at that time was thinking how many people would have given up,” he says. “I always thought, any second now, this lockdown will end and I will be ahead of the game because of my training.

“I used to Facetime my coach and do boxing sessions like that, I’d be doing all my runs and press ups and everything else I could. I started lockdown at 55kg and came out at 78kg.”

The end of lockdown ushered in a new period of amateur success for the teenager but, with word beginning to spread about his talent, bouts were all of a sudden hard to come by. There were few coaches ready and willing to throw their own prospects in with Atang, who, despite doing all the right things, felt like he was dying on the vine.

Which is why he decided to make the move into professional boxing without ever competing at senior level as an amateur. It means when he makes his debut on July 5, at the Manchester Arena, it will be the first time he will be punched in the face without a headguard on.

“Not if I can avoid it,” he cracks back. “I’ve sparred without a headguard just to get a feel for it. But I want to walk out and give him a free jab straight on the nose and be like ‘ah, yeah, I’ve arrived’. This all excites me a bit more, and it makes me feel like I’m in a proper fight which is what this game is all about.

“I felt like I needed to go pro early so we can learn on the job and go from there. The last club bout I had was three years ago now. I entered the nationals this year but there were no opponents. So I would not have boxed from last November to this September when the Europeans are.

“I just thought, I can’t do this. At this age I can’t have this inactivity. So I thought, why not?”

Turning professional, particularly at heavyweight, without any senior bouts used to be unheard of but another teenage prodigy who did exactly that was Moses Itauma. At 18, he had never had a fight with a man either but he stopped his first one, Marcel Bode, after just 23 seconds of his debut and he has since charged to 12-0, 10 KOs.

All of a sudden, professional newbie Atang is making Itauma, still only 20, seem old but he is keen to pump the brakes on any comparisons with man widely considered the future of the division.

“I see a lot of people comparing us,” Atang adds. “But I think we are in totally different positions. He’s going the faster route, I’m going for the more slow route.

“I think he’s done unbelievably well and I think he’s paved the way for young heavyweights like myself to come through. I look at him and I’m in awe of some of the stuff he does and it’s class to see.

“But the people comparing us should know we’re on two completely different things. It’s an honour to get compared to him but I’m on my own journey, doing my own thing.”

When Itauma turned professional amid much fanfare when he turned 18, there was no secret made of the desire to beat Mike Tyson’s record of 20 years and four months and become history’s youngest world heavyweight champion. The deadline to do that came and went last month.

Atang, in theory, has around two years to accomplish the feat but it is refreshing to hear him laugh off the suggestion.

“That’s not for me,” he says. “I’ve gone early and I want a good few years to mature, mentally and physically. I’m a smaller heavyweight so I’ve got a lot of time to grow and learn the game. I’ll admit I’m in no position to be calling out the big boys yet, but eventually I know that’ll come. I believe in myself that one day it will come.

“And maybe that day will be at Wembley Stadium and there will be a school kid watching just I like was.”

analysis

Fight news

Declan Taylor

Next

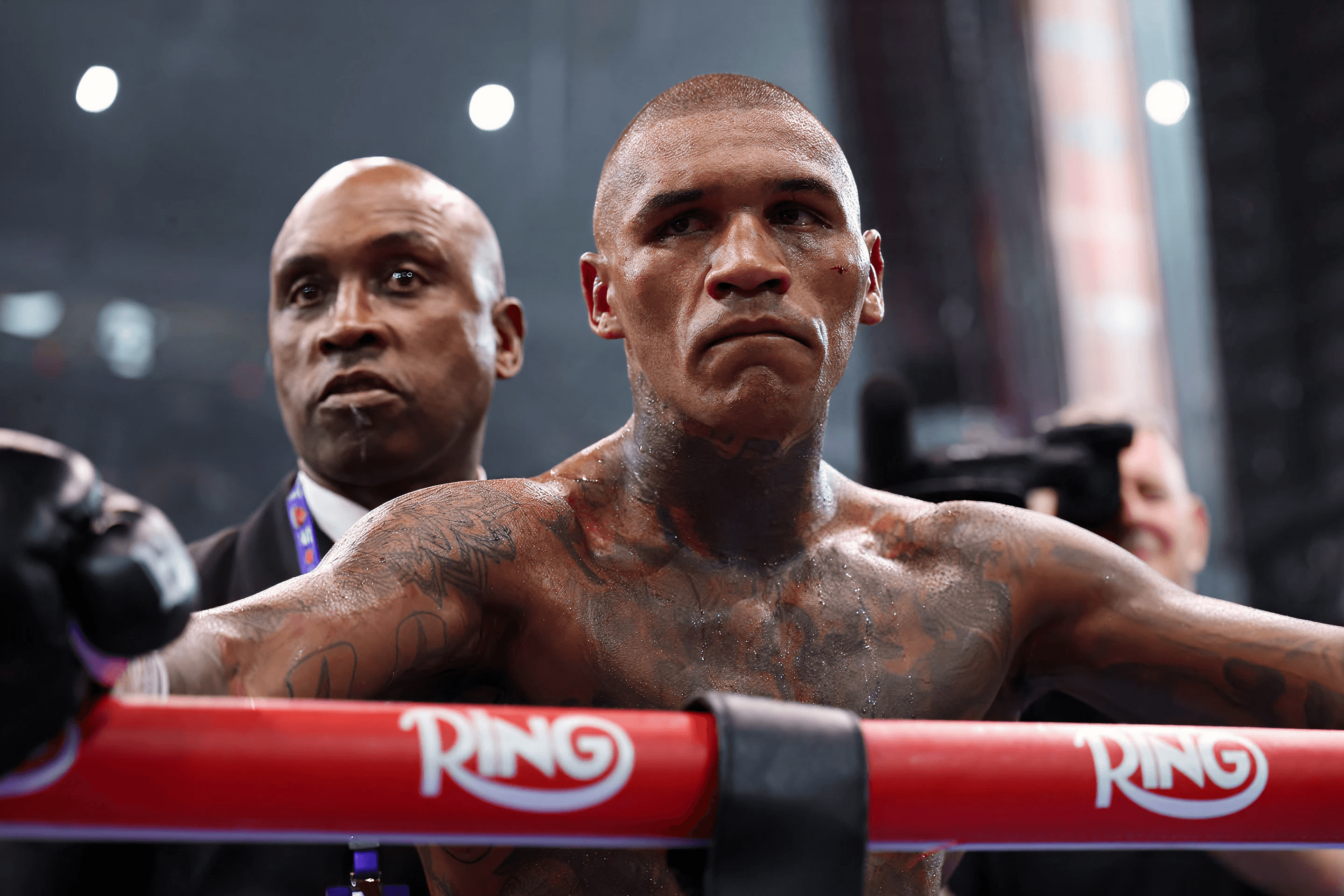

Conor Benn believes he should have won a decision

RELATED ARTICLES

The Ring Roundtable: 5 key questions before the biggest fights on January 31

Latest News

Declan Taylor: Will Josh Kelly's rough ride reach its dream destination?

Latest News

Frank Sanchez-Richard Torrez reach deal on IBF eliminator, late March targeted

Latest News

RELATED ARTICLES

The Ring Roundtable: 5 key questions before the biggest fights on January 31

Latest News

Declan Taylor: Will Josh Kelly's rough ride reach its dream destination?

Latest News

Frank Sanchez-Richard Torrez reach deal on IBF eliminator, late March targeted

Latest News

Can you beat Coppinger?

Lock in your fantasy picks on rising stars and title contenders for a shot at $100,000 and exclusive custom boxing merch.

Partners