Mar 24, 2025

9 min read

The life and career of “Pitbull” Livingstone Bramble was one of constant dichotomy. His career inside the ring would represent the wildest dreams of most who dare to lace up the gloves, and the nightmares of those with the disposition to keep them lace...

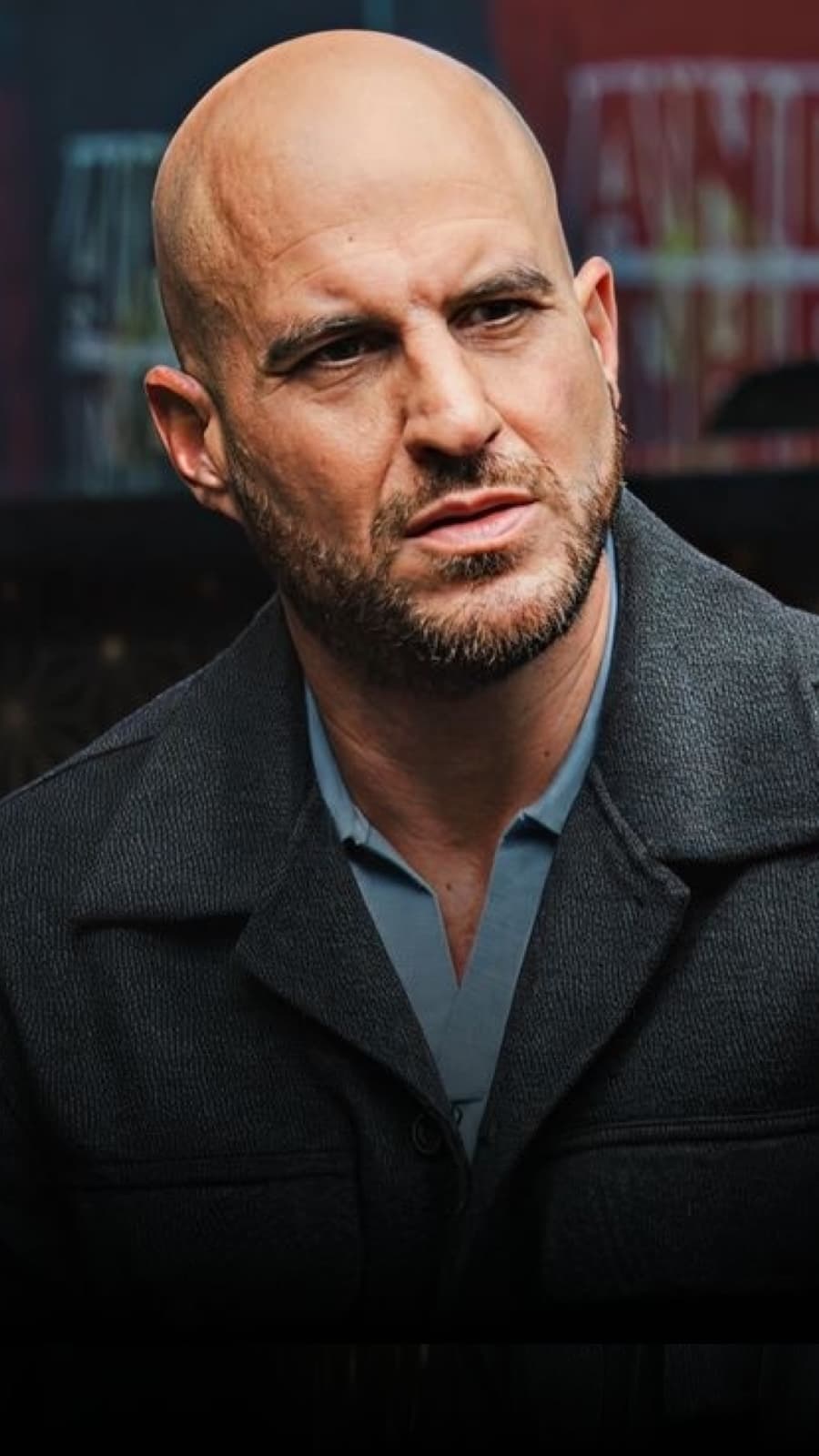

The life and career of “Pitbull” Livingstone Bramble was one of constant dichotomy. His career inside the ring would represent the wildest dreams of most who dare to lace up the gloves, and the nightmares of those with the disposition to keep them laced for too long. He was a menacing bruiser in the ring and a compassionate animal caretaker and lifelong vegetarian outside of it. One of the sport’s most eccentric and flamboyant characters and one of its most famous recluses. One of the sport’s best and most visible fighters at one time, and one of its many props used for record enhancement in obscurity.

He was a boxer of a bygone era, one of the last 15-round championship fighters, and one ahead of his time. One can only imagine how a world that incentivizes shock value would have monetarily rewarded Bramble’s many quirks.

On Saturday, March 22, Bramble passed away at the age of 64, a story overshadowed, as he himself so often was for the vast majority of his career, by the passing of George Foreman the same day. But the two share more similarities than just the same resting date on their tombstones. Like Foreman, Bramble was a character crafted in an era when mystique could truly thrive, when apocryphal tales were like catnip to writers and broadcasters, and the stories it would yield like a stronger herb of Bramble’s preference to their audience.

In September of 1984, Bramble graced the cover of Ring Magazine with his rasta beret on his head and both his WBA lightweight title and pet snake named Dog--the corresponding pet dog named Snake was no doubt on-site with him for the photoshoot too. Three months prior, Bramble had defeated Ray Mancini, perhaps the sport’s biggest cable television draw at the time, and captured the title in one of the decade’s best bouts.

The victory, combined with Bramble’s pre-fight antics and seemingly mythical backstory turned him into both a near-millionaire and phenomenon overnight. In the build-up to the Mancini bout, Bramble’s story became known to the wider sports audience for the first time. They learned of his zoo-like collection of animals, his advocacy for cannabis use, his eschewing of meat products and his Rastafari religion. As one might expect, none of these things were commonplace in the United States in 1984, and Bramble was treated as an oddity. Bramble, at the encouragement of manager Lou Duva, leaned even further into this, bringing a “witch doctor” to place a “voodoo spell” on Mancini, who stood in the back corner of the room during the fight press conference holding a book of “spells.” As it turned out, the man was Bramble’s old basketball pal Matthew Marvin, who was earning his master’s degree at Cal State-Los Angeles at the time, in costume.

While many reporters and fans either believed or played along, those back home in his birthplace of Saint Kitts and Nevis and his homeland of the U.S. Virgin Islands laughed along with the hoax. Marvin broke character and told classmates and students that it was a joke, and Virgin Islands senator Bert Bryan told Bramble’s biographer Brian D’Ambrosio that his people “knew it was a joke right away and laughed along with it.”

Bramble proved to be no joke inside the ring, fighting nothing like the 4-1 underdog he was listed as, bloodying and stopping Mancini in the 14th round, spoiling Mancini’s tentatively planned showdowns against Hector Camacho and Aaron Pryor and calling them out himself. Rather than wait around for them, or for the Mancini rematch, he scored a stay-busy win over Edwin Curet before matching with Boom Boom once more. In the rematch, Bramble proved he was no fluke, edging Mancini in another bloody battle that also holds the distinction of the first event ever counted by CompuBox, outlanding him 674 to 381.

"I was not getting hit to the body, I was getting hit on the elbows. That's what everybody thinks, I have no body when I go like this," Bramble told Al Bernstein in the ring afterwards, demonstrating his frame defense. "I've got a 74-inch reach, that makes up for the protection of the body."

After Bramble thrashed Tyrone Crawley in his second title defense, KO Magazine eventually rated him the third best pound-for-pound fighter on the planet, and it was a forehone conclusion that he would be the one facing Camacho in a multi-million dollar showdown. Just as Mancini proved to be a perfect narrarive foil for Bramble—Rastafarian vs. Christian, eccentric vs. straight-laced—Camacho presented a perfect alternative as well. Bramble dropped the voodoo act and broke kayfabe to reporters admitting it was a hoax, but was still plenty peculiar. As he prepared to face Edwin Rosario in a double bill with Camacho facing Cornelius Boza-Edwards (the express purpose of the event not hidden at all with Bramble and Camacho’s faces being the only ones, side-by-side on the poster), he trained in lavender tights, practiced aerobics to Michael McDonald and Hall and Oates, and walked around with his pet monkey Wave. He espoused his healthy lifestyle in contrast to Camacho’s wild partying ways, as the former library assistant revealed his dream of having a farmland lush with mangoes and avocadoes by the end of 1989, one so vast and plentiful that he would no longer need to drive a car, just ride his bike to and from the various plants.

Rosario would stop Bramble in two rounds, bringing to an end Bramble’s run as an elite fighter. It’s here that the telling of Bramble’s career tends to stop, as if he faded from the public eye immediately afterwards. His days as a magazine cover star were certainly over, but his time on our television sets would last—for better, but mostly for worse—for another decade.

The long, but eventually precipitous decline of Bramble’s career is generally remembered most for his brief usage of the names Ras-I-Bramble and Abuja Bramble, but there were some highs—no pun intended—baked into the lows as well. In 1991, Bramble deserved a win over Oba Carr in one of the worst robberies of the decade, before Carr went on to greater television exposure. His 1993 bout against Rodney Moore was, according to J. Russell Peltz who spoke to D’Ambrosio for Bramble’s bio, the first event at the legendary Blue Horizon in Philadelphia to be sold out in advance, with no tickets available at the door.

It was a year prior in 1994 that the mainstream boxing audience mostly said goodbye to Bramble, as he dropped a one-sided decision to Buddy McGirt on HBO. At the time, Bramble was 36-12-3, but was still hoping that a win over McGirt would give him a shot at pound-for-pound number one Pernell Whitaker rather than McGirt.

“He said to be in so many words that he's not relying on his power, his physical ability anymore, he's started to reach inward, for spiritual strength, and sometimes when you reach inwardly, you get enough strength to take you over the top,” said Foreman, who was on commentary, in the broadcast intro to the bout. Seven months later, Foreman would upset Michael Moorer, perhaps summoning the same strength he saw in Bramble.

Try as he might, all the way to 2003, Bramble could never produce a Foremanesque miracle comeback. His later years were a mishmash of periods with poor management and self-management, an array of fights on short notice and off the beaten path. Even in 1999 after knocking out Paul Nave at the Marin Center in San Rafael, CA, he spoke of wanting a fight against Oscar De La Hoya—at the time the sport’s biggest star by many magnitudes, dozens of degrees of wattage above Bramble and fighting in arenas ten times the size of the theatre in the sleepy town.

His tethering to the sport was seemingly buoyed by a variety of factors. Bramble seemed to need the sport, both in his soul, but also financially, as he bounced between living in various locations between New Jersey and Nevada, making occasional stops back home on the islands for easy comeback fights and spiritual refuge. As he described to Al Bernstein following the Mancini fight, he had the genetic structural ability to take care of himself in the ring, the ability to absorb shots on his arms. As time went on, the fissures in the guard began to widen, as he endured four more stoppage losses following Rosario, but those nights were still in the minority. When those nights did happen and the fissures became full-blown cracks, like in his frightening knockout loss to Shannan Taylor in 1995, Bramble would always claim he was hit behind the head, never willing to admit that his chin had betrayed him.

“I’m not going to let one cold vibe stop my boogie,” Bramble told the South Florida Sun-Sentinel in 1986. “And that’s been the story of my life.”

Bramble’s fighting career ultimately ended in obscurity in 2003 with a six-round unanimous decision loss to Armando Robles at the Centro Civico Mexicano in Salt Lake City. As he walked out of his dressing room, there were no reporters there waiting to hear his tales anymore, no press conference for him to hold court, just volunteers packing up the folding chairs.

Bramble spent his final years in Las Vegas, drawn back to Nevada after a stint in upstate New York. Glaucoma hampered Bramble’s vision, he remained in fantastic physical condition. Even into the 2010s, Bramble would participate in the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s annual 5K race, the Nate Race, and as an avid marathoner, would frequently place first in the “boxer’s division,” beating out active competitors well into his 50s.

Although Sin City was the ideological opposite of Bramble’s dreamland, it was warmer than his previous upstate New York abode. His apartment had no room for mango trees, but enough for another new collection of pets that could live indoors. It didn’t need room for most of his boxing memorabilia—most of that washed away in Hurricane Bertha in 1996 anyway—but it had proximity to boxing, which he seemed to need, and love, above all else.

The same kind of topical storm that took most of his memories was also how his dreams were born. Bramble entered the world, literally, as Hurricane Donna was hitting Saint Kitts. Six years later, his cousin Battling Douglas, gave him and his brother Frederick a pair of boxing gloves. They would each put one glove on, and would spar under Douglas’ supervision.

"I didn't always win," Bramble told Franz Lidz of those sessions in 1984, "but I didn't ever quit."

Analysis

Noticias de combate

Next

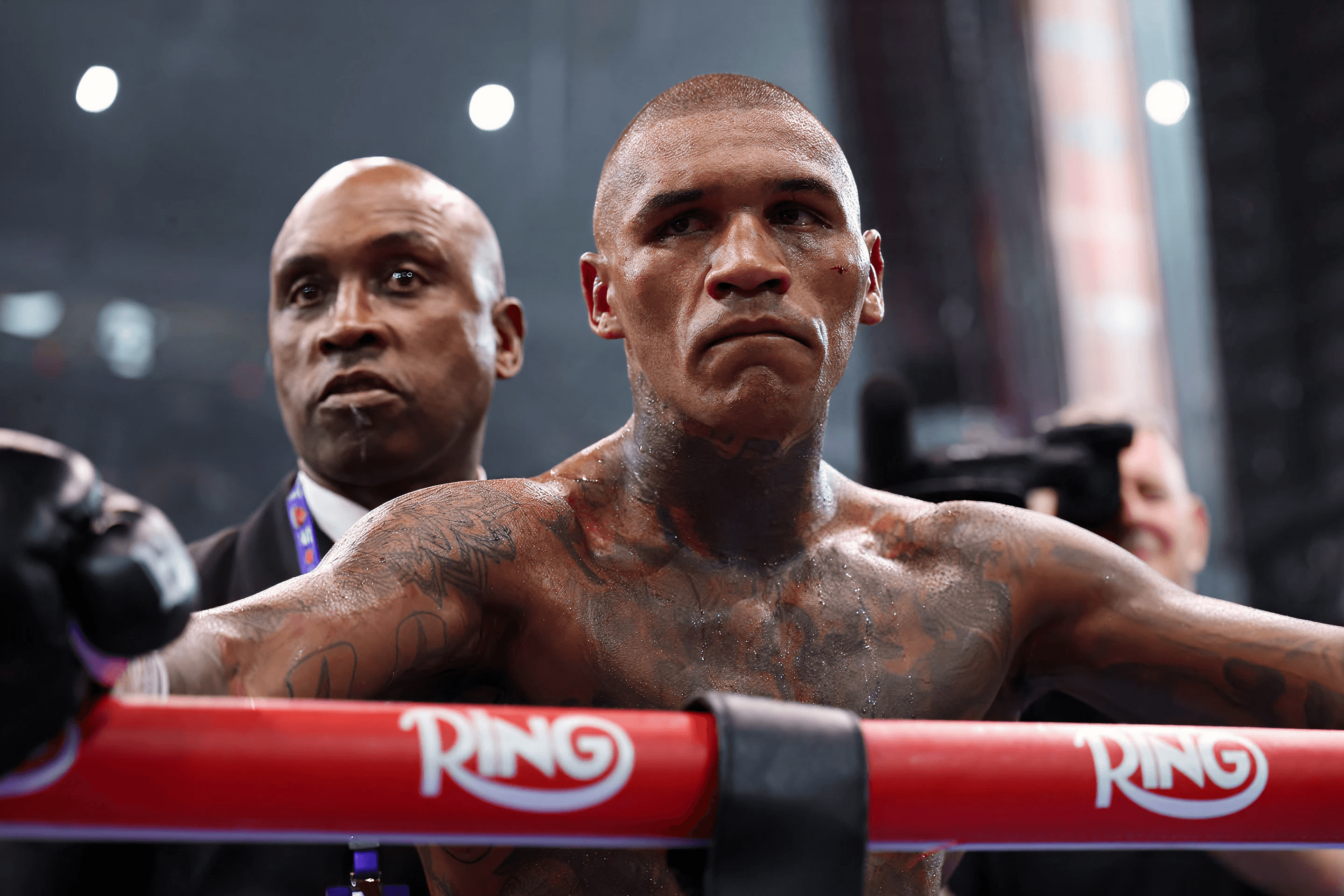

Conor Benn believes he should have won a decision

Can you beat Coppinger?

Lock in your fantasy picks on rising stars and title contenders for a shot at $100,000 and exclusive custom boxing merch.

Partners